It’s never too early, or too late, to start saving for your retirement.

Whether you’re a long-time speech-language pathologist or just out of your CF Year and starting your first position, you can implement several strategies to put you on track for a financially safe and secure retirement.

First, Download Your Free Resources…

- What is the right retirement plan for my private practice? [PDF Flowchart]

- Can I make a deductible IRA Contribution? [PDF Flowchart]

- Should I rollover the balance from my previous employer’s 401k or 403b? [PDF Flowchart]

You might also enjoy our podcast episode on why so many SLPs fall behind when saving for retirement…

Sources for Your Retirement Income

Essentially, your retirement income equation looks like this:

Let’s look at each part of the equation a little bit closer.

Guaranteed income is money you receive every month that you can depend on, no matter what.

Social Security is an excellent example of fixed income. If you’re an employee or a business owner who has taken a salary, then a portion of your income goes toward paying the Social Security tax. Once you reach 62, or if you have other qualifying conditions, you can start receiving Social Security income. Remember that the longer you delay starting to draw Social Security, the bigger your monthly checks will be.

Pensions are also another source of fixed income. You may have worked for an employer that provided you with a pension as a benefit. This is particularly common if you were an SLP that worked for a school system. If you are eligible for pension benefits, you’ll have important choices to make about when you want to start receiving benefits and who will get your survivor benefits.

At some point, you may have also set up an annuity. These are structured so that you will receive a guaranteed income payout at some point in the future, usually ten years or more down the road. You can also buy an immediate annuity that will give you guaranteed income starting right away.

You generally set these up by depositing funds into an account that grows over time. As the account grows, the income base (the amount you will receive) will also increase. The amount you withdraw is typically 4 to 6 percent of the base value each year. The exact amount depends on your age when you start your withdrawals and the terms of your contract.

Consider a bond ladder. In simple terms, you buy a portfolio of bonds that mature over different dates that laddered over time. Guarantees are backed by the issuer. You may lose money if sold prior to maturity.

Variable income typically comes from the money you’ve been accumulating in retirement accounts during your working career. These accounts include 401(k), 403(b), IRA, Roth IRA, and other similar investment instruments. Once you retire, you’ll transition this money into a monthly income stream. The exact amount is variable based on the performance of the particular investments you have.

As you get older, the tendency is to move your variable income sources to more conservative investments to protect your base of funds. An advisor will help you set milestones and monitor your accounts as well as market conditions to make sure you don’t sustain major losses late in the game.

Keep in mind that the right mix of stocks is also a hedge against inflation. If inflation grows at 2-3% annually, you’ve got to increase your income by that much to stay even. Find your comfort level for the amount of risk that’s right for you, but don’t neglect to factor in this variable.

Consider investing in blue-chip stocks that yield dividends, but don’t chase the highest yields, which might be riskier. Mutual funds that focus on dividend-paying companies may be a way to go.

One way to control your variable income is to control your variable spending. Just because you’re retiring and have more time to spend your money does not mean that’s what you should do. Set a budget that allows you to live within your means. Budget for recreation, entertainment, and vacations, but don’t go beyond what’s reasonable for your situation.

A big part of adjusting your variable spending is to consider moving to a cheaper locale. Downsize to a smaller house, a vacation home, or move to where the cost of living is less, and you could save a lot of money in a short period of time.

Other income can be generated in several possible ways. Just because you’ve “retired” does not mean you have to stop working altogether. You can keep working part-time or move on to something else that you enjoy. Consider becoming a consultant, taking on limited practice hours, or going into teaching to supplement your income.

This is a healthy outlet for you as well. Retirement can be difficult if you go from a million miles an hour to zero in one big move. A transition is a much smarter and more gentle approach.

If you’ve done well, you may have made real estate investments that can continue to pay you in retirement. They may require some “landlord” attention from time to time, but this is more than offset by the fact that they generally appreciate over time and provide a significant guard against financial hardships you may encounter. You may even want to consider renting out your primary home as part of a downsizing strategy.

Other income may come from a spouse who wants to continue to work, or from an inheritance that could land in your lap at any time. A few people have even published books in retirement, generating royalty income over time.

How Much Money Will You Need to Retire? Here are 20 Questions to Ask

Asking how much money you’ll need to retire is like asking “how much does a car cost?”

The answer, of course, is that it depends.

Since it’s your retirement, you need to be the one to start thinking about what the answer is. But you don’t need to do it in a vacuum. You should have detailed discussions with your spouse, your immediate family, financial advisors, and others who can help craft a plan that will answer this critical question.

So, where do you start?

Here are 20 questions that all SLPs should ask to start developing a framework to guide your efforts.

- What age will you retire?

- How long do you think you’ll live in retirement?

- What are you doing to protect your assets from health issues in retirement?

- What kind of lifestyle do you want in retirement?

- How much will that lifestyle cost over the course of 20 years? 30 years? 40 years?

- How much will you need to spend on necessities?

- How do you want your investments to perform?

- How aggressive do you want your investments to be?

- Have you considered what an optimal mix of investments looks like for you?

- Is there a specific retirement income goal?

- What are all your sources of income?

- Are you an owner of any other business ventures?

- Do you want to continue to work or consult part-time after you retire?

- How do you want to take care of your family members and your estate needs?

- If your retirement is going to be funded through the sale of your business, what things do you want to do to ensure your employees are taken care of?

- What are the tax implications of your possible plans?

- Do you want to downsize from your current home? If so, what are your options?

- How hands-on do you want to be with your portfolio?

- When should I start taking Social Security?

- Is there a gap between the retirement you want vs. the retirement you can afford? If so, how do you close it?

Avoiding Some of the Main Reasons SLPs Fall Behind in Saving for Retirement

There are many legitimate reasons why you may not be saving enough to fund the kind of retirement you want to enjoy. However, with some modified planning, targeted goals, and disciplined effort, you can create habits that will change your short- and long-term retirement approach.

The first step is recognizing what the main reasons are why you’re falling behind. Here are some things that could be impacting those efforts.

Prioritizing your financial goals. There is a reason personal finance is called “personal.” Every individual has to prioritize what is important to them financially. If you want a bigger house, a new car every few years, nice vacations or want to fully fund your child’s education, those all come at the expense of something else.

For many people, they put off fully funding their retirement to a later date. The adage of, “You can save for anything, but you can’t save for everything,” needs to be a prominent part of how you approach retirement.

A little bit of debt is okay. But driving up debt in a way that sacrifices your future is not.

Not having a plan. Your goals should be part of an overall structured financial plan. You can adjust as your life changes, but without a financial roadmap, how will you ever know where you need to go?

Missing an employer match program. If you work for an employer, and they offer a matching program for their retirement plan, you are missing a tremendous opportunity to increase your savings.

A match program works like this: If you earn $100,000 and the company offers a 100% match on the first 3% of savings into the retirement plan, and you save $3,000 (3%) into the plan, the company will deposit an additional $3,000 into the plan. Your retirement savings total just became $6,000. You magically doubled your money just by participating.

When you do that early in your career, those funds on account have additional time to grow on their own, doing more of the heavy lifting for retirement on your behalf.

Starting too late. When you’re young, you sometimes feel like you’re going to live forever. You live in the moment without much thought for 20 or 30 years out. It’s common. It’s also a trap that steamrolls over time.

When you start saving for retirement late, you miss out on the magic of compound interest.

Not paying attention to fees. It may not seem like a big deal, but fees add up over time. Sometimes you can control fees, and sometimes you can’t.

If you are not controlling costs, it can cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars over your investment lifetime.

One way to trim fees is to look at the expense ratio of funds in which you are invested. Some funds can cost 0.1% and others can 2.0%+.

Dipping into your retirement account early. As your retirement pot grows, you may be tempted to tap into it for a new car, a bigger house, or a second vacation home. No matter how you justify it, you not only lose retirement funds, you will be hit with fees and early withdrawal penalties, plus you’ll lose the compounding effect. This is where discipline is critical.

Taking a hands-off approach. You need to monitor and rebalance your portfolio at least once or twice a year, depending on market conditions and in consultation with your advisor. You can’t be efficient if you don’t know and understand what’s going on.

Lousy tax planning. If you plan the right way, you’ll get to keep most of what you’ve saved. If you don’t, then the government will say thank you for your contributions to the country. Understand tax implications and what you need to do to minimize the bite.

Am I On Track to Retire When I Want?

You won’t know for sure until you run the numbers.

So, how do you do that?

Using the formula above (Fixed Income + Variable Income + Other Income = Retirement Income), you need to concentrate on how much variable income you’re going to receive.

If you want to have an annual income of $100,000 when you retire, and you know you’ll have $50,000 of fixed income that you can count on every month, then you need to figure out how to bridge the remaining $50,000 to meet your goal.

If you decide not to work or consult in retirement, you can eliminate other income as a source. Financial professionals typically use the 4% withdrawal rule as a measuring stick for planning purposes. This means you’ll need 25x your income from which to draw.

In this case, take the $50,000 gap, multiply it by 25 (25 years x 4% = 100%) to produce a figure of $1.25 million in a variable income pool of money you will draw from in retirement.

This goal is also often expressed in an equation:

Bottom line…the more you save, combined with the interest and rate of return you receive, help you to reach your goal quicker.

When is it Best to Start Saving for Your Retirement?

Answer: Now.

If that’s not practical, then as soon as possible.

To help put things in perspective, consider The Rule of $20. It’s simple and states that for every $20 you save, it will generate $1 of retirement income annually, adjusted for inflation.

Translated, that means if you have $1 million saved heading into retirement, you can expect to generate about $50,000 a year in annual retirement income. The Rule of $20 projects funds to deplete at age 90 for an investor who retires at 65. Keep in mind, this does not take into account other sources of retirement income (fixed and other income).

Selling Your SLP Private Practice to Fund Your Retirement

If you’ve been in practice for many years, then you have probably built a sizeable practice. That means you’ve created a significant asset that can be the cornerstone of funding your retirement.

In fact, according to a CNBC poll, 78% of small business owners say the proceeds from the sale of their business will fund 60-100% of their retirement income.

Unfortunately, the flip side of this is that 98% of owners do not have an accurate valuation of what their business is worth.

That disconnect makes it nearly impossible to create a viable retirement strategy. You can’t plan for the future if you don’t know what your future looks like.

The valuation of your business is too important to use general rules of thumb or non-industry comps. There are methodologies to give you specific estimates of value and valuations specific to owning a speech-language pathology private practice.

Determining the value of your SLP practice is so critical, that I’ve devoted an entire podcast to this subject: SLP Money Episode 3: Why You Must Know the Value of Your Private Practice with Jason Early.

The sale of your business can be a pivotal event to help close the gap between the amount of money you have saved and how much money you will need to retire.

In simple terms, the concept looks like this:

To get a formal valuation of your SLP, you’ll need to retain an accredited valuation expert. Expect the process to take as long as six weeks at a cost of at least $8,000 or more.

As I discussed with Jason in the podcast, obtaining a formal valuation can be a laborious process. For the majority of speech private practices, a fair estimate of value is sufficient to begin this planning process. With a fair estimate of value in hand, you can also structure insurance coverage at appropriate levels, structure a business plan to keep growing your practice and use the valuation to secure future business loans.

With a fair estimate of value, you’ll know exactly what your gap is for retirement, and you can then realistically go to work at closing that gap.

Your valuation will also play a role in determining whom you’d like to take over your business. You may want a family member, key employee (or group of employees), or a third-party buyer to be your successor. Each comes with pros and cons you’ll have to consider going forward.

Your exit plan should also include how to deal with unexpected events along the way. Create solutions for what happens if you or a partner passes away, or you get a chronic illness that keeps you from working. Decide how you’ll handle a slow-down in business, or if an unforeseen event shutters your practice for an extended period (i.e., Covid-19).

You can mitigate many of these situations with some smart risk planning strategies. Consider life insurance, disability insurance, excess liability insurance, and other protections that will protect the value of your practice.

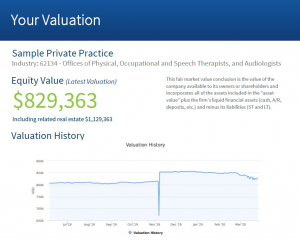

A Sample Fair Estimate of Value

After you complete your practice’s sale, you’ll need to decide what to do with the proceeds. Depending on your long-term goals and current finances, you can invest it in a mix of fixed and variable income-producing assets ranging from annuities to mutual funds, starting another business, or income-producing real estate, as examples.

Tax Planning to Minimize Taxes in Retirement

For tax purposes, there are three types of retirement accounts, and each one treats taxes differently.

- Tax-deferred: Money goes in pre-tax and goes out post-tax.

- Tax-free: Money goes in post-tax and goes out without being taxed.

- Taxable: Money goes in post-tax, and you have to pay capital gains and dividends tax annually.

How you allocate money from a tax perspective now can potentially save you a lot of money later on. Understand that these aren’t one-time set it and forget it decisions.

For example, if you have a year where household income is much lower than usual (i.e., pregnancy, temporary job loss), you may want to consider engaging in proactive tax planning.

Some of your retirement income will be taxed. This includes a good chunk of your Social Security benefits, the money you take out of your traditional IRA and 401(k). Also, investments you have in a brokerage account may face taxes on capital gains and dividends.

To trim your tax bill in retirement, consider these options:

Put money into a Roth IRA. Your contributions and the money you earn in that account will be withdrawn tax-free in retirement. Hint: You can convert a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA with something known as a backdoor Roth IRA. You do pay taxes on your money before you put it into your Roth IRA, but you may be in a better place to do that while working.

Pay off your mortgage. By the time you hit retirement, most of your payment is against the principal of the house, so you don’t get a tax break from the mortgage interest deduction. Without a hefty house payment, you don’t have to withdraw funds from retirement accounts that could trigger tax payments.

Trim your capital gains taxes. If you have stocks that have appreciated quite a bit, hold off selling those stocks until your income (and resulting tax rate) is lower.

Manage your retirement account withdrawals. If you have a year in a lower tax bracket, consider withdrawing money from a taxable account such as a traditional IRA or 401 (k). If higher tax bracket years, take cash out of your Roth because you’ll be in a higher bracket, but won’t have to pay taxes on a Roth withdrawal.

Consider charitable donations. If you turn 70 ½ and must start taking money out of your IRA, consider donating it to charity. That strategy lets you avoid income tax on up to $100,000 per year. You can use all or a portion of that donation to count for your required minimum distribution from your IRA.

What About Legacy or Charitable Intentions?

Every retirement account is eligible to receive a beneficiary designation, which is the entity that gets the balance of your account when you pass away. It can be a spouse, children, a university, your favorite charity, or anyone else you want to have the funds.

The important thing to remember here is that beneficiary designations supersede what you may have in your will or other estate planning documents. If you are divorced, it is essential to update your beneficiary designations. Otherwise, your ex-spouse may be the unintentional recipient of funds that were intended for someone else.

The Retirement Planning Solutions and Strategies I Help SLPs Deploy

As you move through your career, your guaranteed income choices are limited and can be managed or modified with relatively little effort. They are less dynamic than variable income sources, which require more oversight. There is also a confusing array of choices and deciding the right path to follow is a challenge.

Because each SLP and their financial profile is different, the solutions that I put together are highly individualized. Together, we can craft an appropriate strategy to ensure you meet your retirement goals. There are many different options to consider, each with specific benefits that may improve your unique situation.

Even if you are in your 40s or 50s and feel you’re behind in saving for retirement, some strategies are a way to savings and put away a lot of money over a relatively short time.

Let’s look closer at what some of those common investment plans are and why they may be the right choice for you.

Defined Contribution Plan – This is a plan that is typically tax-deferred where employees contributed a fixed amount or percentage of their income to fund their retirement. In some cases, employers will match the contribution. The 401(k) is perhaps most synonymous with the defined-contribution plan, but there are other options.

Income tax is ultimately paid on withdrawals, but not until retirement age (a minimum of 59½ years old). The tax-advantaged status of defined contribution plans generally means balances grow larger over time compared to taxable accounts.

These plans place restrictions that control when and how each employee can withdraw from these accounts without penalties.

Unlike defined benefit plans, these plans are not guaranteed by an employer. Participation is both voluntary and self-directed. Employees may not be financially savvy and have limited or no other experience investing in stocks, bonds, and other asset classes. As a result, some individuals may invest in improper portfolios instead of a well-diversified and limited-risk portfolio.

Defined Benefit Plan – This was the predominant form of employer-sponsored retirement plan until the 401 (k) was introduced. It provides a monthly retirement benefit based upon a formula that considered an employee’s earnings history, tenure of service and age. Contribution levels may be substantially higher than defined contribution plans (e.g., 401(k), profit-sharing, etc.).

A defined benefit plan favors older, highly compensated employees.

It can be more expensive to administer than a defined contribution plan. Contributions are mandatory each year, subject to minimum funding rules, with IRS penalties if not funded.

It is best for business owners and highly compensated employees who are more focused on retirement (usually 10 to 15 years or sooner) and businesses looking for increased tax deductions as well as owners looking to make up for lost time in accumulating retirement income.

Cash Balance Plan – A cash balance plan is a variation of a defined benefit plan, seeking to combine the attributes of a defined contribution plan with a defined benefit plan. Each employee has a hypothetical account earning a fixed rate of interest on the employer’s contribution, which is typically based upon a percentage of the employee’s earnings, to determine the employee’s retirement fund at retirement age. The rate of interest can vary from year to year.

It may be combined with a profit-sharing 401(k) plan. Level funding provides for more stable contributions that makes budgeting easier. It is more expensive to administer than a defined contribution plan, and contribution is mandatory each year, subject to minimum funding rules, with IRS penalties if not funded.

It is best for owners in mid-career, with ten years to retirement and an age that is ten years, on average, older than the other non-highly compensated employees. It is also best suited for businesses with multiple owners of different ages, and businesses that want to tier benefits to different types of employees.

Roth IRA – This is a variation of the traditional IRA and uses after-tax contributions but allows for tax-free growth and distributions. It allows for tax-free growth, and qualified distributions are tax-free.

There are a few drawbacks, such as eligibility that is phased out for high-income earners.

Contributions may not be used to purchase life insurance and contributions may not be as large as other types of plans.

SEP-IRA – The SEP-IRA is one of the most popular retirement plans for self-employed individuals and small business owners due to its simplicity and lack of administrative costs. Employer contributions are used to fund individual IRAs for the plan participants.

Unlike other employer-sponsored plans, there are no annual IRS filing requirements. Also, depending on the formula used, there can be no administration costs. It is funded solely by employer contributions, and participants are immediately vested in 100% of the employer contributions.

There are a few downsides. This plan may not include life insurance as a plan investment, and distributions before age 59 1⁄2 may be subject to an early withdrawal penalty. Also, the participant bears the investment risk.

401(k) Plan – This is the most common form of an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan. It allows a pre-tax deferral of compensation, as well as employer contributions, either as a “matching” component or as a profit-sharing contribution. Contributions and distributions follow many of the same rules as Roth IRAs, but with life insurance and loans allowed, and the larger 401(k) limits on contributions.

This plan allows for pre-tax and after-tax deferrals. It also allows for catch-up contributions for those age 50 and older.

However, owners and other highly compensated individuals may not be able to contribute the maximum allowable by law due to low employee participation and deferral rates.

The plan also needs a third-party administrator who performs the necessary testing and governmental reporting. The participant also bears the investment risk.

Safe Harbor 401k plans to ensure all employees are treated fairly and not overly burdened by expensive administrative costs. It allows the owner and other highly compensated employees to defer the maximum allowable by law regardless of what the rank-and-file (non-owners and non-highly compensated employees) are deferring.

Fully Insured Plan – This is a defined benefit plan that is funded solely with a fixed annuity contract or a combination of a fixed annuity contract and a life insurance policy. The employer shifts the investment risk to the insurance company that provides insurance and annuity contracts.

This allows the plan to avoid many of the funding requirements of traditional defined benefit plans, as well as administrative requirements. It also allows for more substantial contributions, making them very popular for small business owners who have relatively few years left until retirement.

It favors older, highly compensated employees. A fully insured plan is also not subject to market volatility, so there is no investment risk, and no under or over funding.

The fully insured plan is best for owners who are risk-averse and looking to make up for lost time in accumulating retirement income. It’s also well suited for owners and other highly compensated employees seeking a recovery plan due to market losses suffered by their other retirement accounts from economic downturns and recessions.

Key Retirement Planning Terms to Know

Part of learning about retirement strategies is understanding the lingo that a financial professional may throw out, or phrases you’ll see when reading up on the subject. Here are several common retirement planning terms you may come across as you educate yourself.

Adjusted Gross Income. An interim calculation to determine tax liability. It is determined by subtracting certain allowable adjustments from gross income.

Age Rule. An individual must be under 70½ for the entire year to be eligible to make a regular contribution to an IRA.

Asset Allocation. The process to decide how investment funds will be divided among asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and cash reserves.

Capital gains. This is the difference between how much something is worth now versus how much it was when originally purchased. A capital loss is a decrease in the asset’s value since you bought it. You pay taxes on both short-term capital gains (a year or less) and long-term capital gains (more than a year) when you sell an investment.

Compounding. Earning money on a principal investment and its interest, widely considered to be one of the best ways to create wealth.

Death Distribution. The payment of IRA funds to a beneficiary upon the death of an IRA owner.

Deduction. An expense allowed by the IRS to be subtracted from an individual’s gross income before figuring a person’s taxable income.

Direct Rollover. Moving funds from a qualified retirement plan into an IRA without the account owner taking receipt of the funds.

Distribution. Withdrawing funds from a retirement savings plan.

Dollar-Cost Averaging. Growing assets by investing a fixed amount of dollars in securities at set intervals, regardless of stock market movements. (i.e. $1,000 per month set on autopilot).

Early Withdrawal. Taking out funds from an IRA, a 401(k) plan, or any tax-qualified retirement plan, usually before age 59½. Most early withdrawals are subject to tax penalties.

Earned Income Rule. The rule regarding eligibility to contribute to certain types of IRAs. For a Traditional or Roth IRA, an individual must have earned income that includes wages, salaries, bonuses, tips, commissions, and taxable alimony, among other types.

Excess Contribution. An IRA contribution that exceeds the maximum limits permitted by law. Penalty taxes apply for each year an excess contribution exists.

Fiduciary. The legal obligation of a professional adviser, such an attorney or a CFP, to act in clients’ best interests.

Form 5329. IRS tax form on which early withdrawals are reported.

Form 8606. IRS tax form on which non-deductible IRA contributions are reported.

IRA Rollover. Moving IRA funds from one provider or plan to the account owner, and then to another IRA provider. The account owner has 60 days to complete this transaction before the transaction is considered a taxable distribution of funds.

IRA Transfer. Moving IRA funds directly from one IRA provider to another without the IRA owner taking receipt of the funds.

Lump-Sum Distribution. Payment to a recipient of all funds in a 401(k) account or another tax-qualified plan in one taxable year.

Matching Contributions. An employer’s contribution to an individual’s 401(k) account based on the amount the individual contributes.

Qualified Retirement Plan. A Defined Benefit or Defined Contribution retirement plan that receives special tax treatment because it meets IRS requirements.

Roth IRA Conversion. The distribution of assets from a Traditional IRA into a Roth IRA.

Self-directed IRA. An IRA that allows the individual to select the investment options that best fit their investment objectives.

Trusts. A legal arrangement whereby a person gives real or personal property to another person to be managed for the benefit of the giver, which can be another person or a charity.

Vested. For a retirement savings plan employee, this is the gradual granting of ownership of contributions made by an employer.

The Benefits of Having a Financial Advisor Who Knows The “Ins and Outs” of SLP Practices

While there are a lot of similar things, no matter what kind of service business that you sell, there are also some things that are unique to selling an SLP practice as well.

Experience is the best teacher, and you’ll want a “teacher” in the subject that most closely matches what you’ve gone through to grow your practice to a point where it’s a valued asset.

Sure, plenty of financial advisors can help you develop an exit strategy, set up a sensible retirement plan, help you determine the value of your business, and figure out ways to help the right owner finance the purchase.

But all other things being equal, wouldn’t you prefer someone to assist you who understands the mindset of an SLP? That’s the advantage you’ll want and need to help advise you on how to structure the best deal for your particular situation.

Would you like to continue this retirement conversation with us directly?

To help potential clients make an educated and informed decision about our firm, we’ve designed a no-cost, no-obligation four-step process we call our “Plan of CARE” Process. Click the Start Here Button to Learn More.

by

by